Cranberry Weevil

Order: Coleoptera || Family: Curculionidae (weevils or snout beetles) || Subfamily: Anthonominae

Scientific Name: Anthonomus musculus (Say)

- Magnified view of a Cranberry weevil next to a U.S. penny

- Cranberry weevil (on the rim of a 12″-diameter insect sweep net)

- Cranberry weevil (on the rim of a 12″-diameter insect sweep net)

- Pair of Cranberry weevils that are mating

- Cranberry weevil

- A Cranberry weevil resting on a sweep net (photographed June 17th)

- Cranberry weevil

- Cranberry weevil adults on the rim of an empty baby-food jar

- Magnified view of a Cranberry weevil

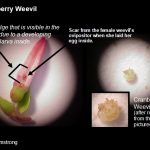

- Cranberry weevil feeding and oviposition scarring damage to an unopened cranberry flower (i.e. pod or bud)

- Another photo showing heavy damage to a cranberry flower caused by Cranberry weevil

- Click for a larger view

- Cranberry leaves with feeding injury caused by Cranberry weevils

- Wild (lowbush) blueberry leaves showing numerous small holes as a result of feeding by cranberry weevils

This tiny beetle is native to North America, and it has a wide host range. Besides cranberry–as its name naturally suggests–it is also found commonly on black huckleberry, wild and cultivated blueberry, swamp sweetbells, staggerbush, dangleberry, sheep laurel, swamp honeysuckle, and on the flowers of chokeberry. It is also called the “blueberry blossom weevil.” It appears that other host or transitional plants surrounding a cranberry bed do typically add to weevil populations by creating reservoirs of weevils.

More than 100 species of the genus Anthonomus occur in North America. A few others of economic importance are the boll weevil (in cotton), the strawberry weevil and the apple curculio.

Pest Status: All snout beetles (except for a few occurring in ant nests) are plant feeders, and many are serious pests, such as the one described here! Most snout beetles, including the cranberry weevil, will–when disturbed–draw in their legs and antennae, fall to the ground, and ‘play dead’ for several minutes, making them very difficult to find. In cranberry, adults are monitored by sweeping (25 sweeps per acre) with a 12″-diameter sweep net. The Action Threshold (AT) has historically been an average of 4.5 weevils per 25 sweeps for the spring generation of weevils, but for the brand new weevils emerging later–the “summer generation”–the threshold is doubled to an average of 9 per 25 sweeps because these weevils are more robust and are therefore harder to kill; thus, it makes sense to wait for a higher level before attempting to kill them when there is less guarantee that the product will work very well. In Maine, most sites have not experienced high levels of this pest, at least not consistently, but it does show up from time to time at a few locations, and sometimes at very high levels, especially in organic settings.

Life Cycle:

Adults (two separate broods): The overwintering cranberry weevil adult (which overwinters in surrounding woods) is about 1/10″ to 1/16″ long, dark red/crimson or a dark red-brown. Like all weevils, it has a snout (or beak), with its antennae arising from about the middle of the snout (see photos). They seldom fly because their bodies are heavy and stout, but when they do, they have been observed to make single flights of up to 75 feet. The weevils that are alive in the spring are referred to as the ‘Spring generation’ in order to distinguish them from the offspring of this generation, which are subsequently hatched out from the eggs that are laid later on, during bloom (these ‘brand new’ adults are thus referred to as the ‘Summer generation’). Spring-generation adults are older and weaker, having had to overwinter, and so they are the ones that are targeted the most in spray programs (sprays on summer-generation weevils have not, to date, been effective). Sweepnet ‘First Dates’ (in Maine) (Spring Generation adult weevils): 6/8/01, 6/13/02, 6/20/07 and 6/2/09, 5/21/18 (Average of these = June 7th)

Eggs: Females will insert a single egg between the petals of a developing blossom during June and July in Maine and Massachusetts. Many of the infested blossom buds (or pods) fall to the ground, some even before the egg hatches. In the lab at the UMass Cranberry Experiment Station, egg-laying was observed in large, fully developed blossom buds. Females will often completely sever the pedicel with their mouthparts after laying their egg inside. But on smaller blossom buds, females tend to only partially cut the pedicel following egg-laying, creating a point of weakness. [The female weevil does this in blueberry as well]. Each female may lay 50 or more eggs in her lifetime of 13+ months. The smooth, round eggs are no larger than 1/16″ and are pale yellow in color.

Larvae: The white, legless grub is approximately 1/9″ long. As it grows, it will consume all of the internal flower parts. The larva then pupates, until it finally emerges as an adult. The entire life cycle–from egg to adult–takes about 2 months and can also be completed on wild and cultivated blueberry.

Control: The cranberry weevil is difficult to control, in part because bees are often present at the same time as the weevils, when sprays are neither sensible nor legal in many cases. Late-water and Fall floods are not effective against it. Sanding provides no benefit, either. Several materials are registered to use against it for non-organic, commercial growers, but in many cranberry parts of the country, cranberry weevil developed a resistance many years ago to some of the broad-spectrum insecticides. For organic growers, one option that has been tried is a quick, 24-hour flood during the last part of June or 1st part of July. The flood may not kill many of the weevils, but it at least floats them off the cranberry bed and provides some temporary relief. Within a week’s time, at least half of the weevils have been observed to find their way back again, though. Still, it may make sense to try this under desperate circumstances. It is a risky maneuver, as a flood that is held for too long may result in the loss of the current year’s crop.

For specific and current control recommendations for Cranberry Weevil (for Maine), please refer to the Maine Cranberry Pest Management Guide.